Change is an inevitable part of business, and effectively managing it can make the difference between thriving and merely surviving. These changes can be due to technological advancements, market shifts, or internal restructuring, and require a robust change management strategy. In this post I briefly outline the change management strategies of John Kotter and Leonard Schlesinger from the 2008 HBR article Choosing Strategies for Change.

What is Organizational Change?

Organizational change refers to the process through which a company or organization undergoes a transformation to adapt to internal or external factors. These changes can be driven by technological advancements, market dynamics, or the need for internal restructuring to improve efficiency and effectiveness. Examples of organizational change include technological upgrades, mergers and acquisitions, and shifts in organizational structure. For instance, upgrade of the ERP system at Siemens, the merger between Disney and Pixar, or Microsoft’s shift from a traditional hierarchical structure to a more agile approach, fostering a more collaborative and innovative environment.

Managing organizational change comes with its own set of challenges. Employees may resist changes due to fear of the unknown or concerns about job security, productivity can dip during transitions as employees adapt to new systems or processes, blending different corporate cultures during mergers or acquisitions can be difficult, requiring time and effort to align values and practices. Implementing change also demands significant resources, including time, money, and personnel.

By understanding the possible challenges and strategies to navigate them, organizations can ensure smoother, if not perfect, transitions and more successful outcomes.

Common Causes of Resistance to Change

According to Kotter and Schlesinger, most organizational changes are met with some form of human resistance. Assessing these correctly is the first step to managing them. The authors point out 4 common reasons for this resistance:

- Parochial Self-Interest: Individuals may resist change if they believe it threatens their own interests or status. For example, an employee might oppose a new project management system because they fear it will make their role less important or eliminate their job altogether.

- Misunderstanding and Lack of Trust: Resistance can stem from misunderstandings about the change or a lack of trust in those implementing it. For instance, employees might resist a new company policy if they don’t trust management’s intentions or don’t understand the policy’s benefits, suspecting hidden motives.

- Different Assessments: Employees may resist change because they believe they have better information or understanding of the situation than those proposing the change. For example, a marketing team might oppose a new sales strategy if they think it doesn’t align with market realities based on their own data and insights.

- Low Tolerance for Change: Some individuals have a low tolerance for change, making them more likely to resist any alterations to their routine. For example, long-time employees might struggle with the adoption of new technology, preferring to stick with familiar processes they’ve used for years.

The 6 Change Management Strategies

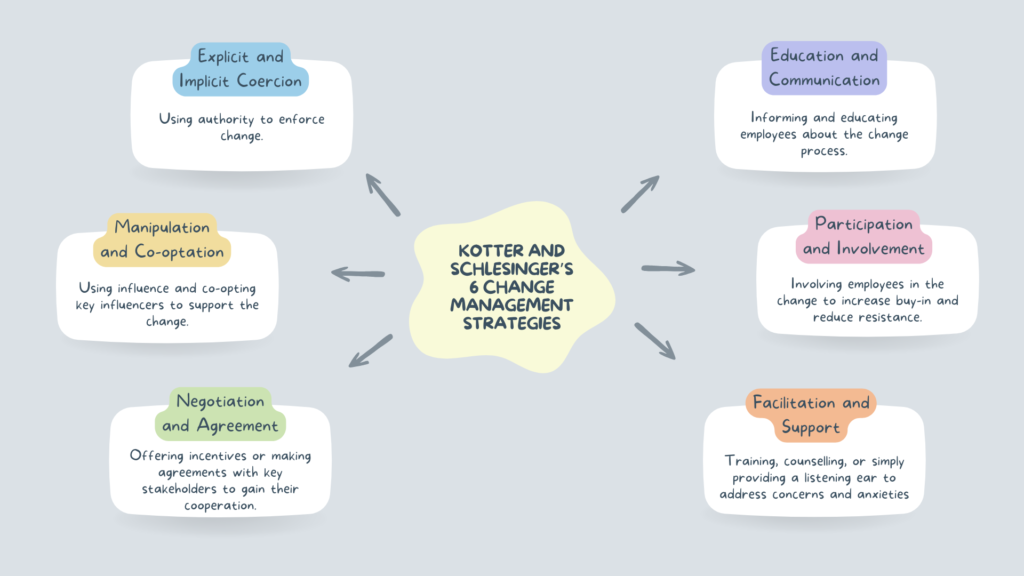

Kotter and Schlesinger provide 6 strategies to address different levels of resistance and support within an organization:

- Education and Communication: This strategy focuses on informing and educating employees about the change process. By providing clear, honest communication, you can reduce misinformation and alleviate fears, helping employees understand the necessity and benefits of the change.

- Participation and Involvement: Involving employees in the change process can significantly increase buy-in and reduce resistance. When people feel they have a voice in the process, they are more likely to support the changes.

- Facilitation and Support: Offering support and facilitation helps employees adjust to change. This can include training, counseling, or simply providing a listening ear to address concerns and anxieties.

- Negotiation and Agreement: Sometimes, securing support for change requires negotiation. This might involve offering incentives or making agreements with key stakeholders to gain their cooperation and reduce resistance.

- Manipulation and Co-optation: This strategy involves using influence and co-opting key influencers to support the change. While it can be effective, it must be used carefully to avoid ethical issues and potential backlash.

- Explicit and Implicit Coercion: In cases where quick action is needed, coercion may be necessary. This involves using authority to enforce change, although it can lead to resentment and should be a last resort.

Each of these methods has its pros and cons, for example, Participation and Involvement is by far the most successful strategy, however it is time consuming and may not be appropriate for changes that need to be implemented quickly. Hence, careful assessment of the situation is advised before selecting the right strategy.

Situational Factors Affecting the Choice of Strategy

According to Kotter and Schlesinger, the choice of change management strategy depends on four situational factors:

- Amount of Resistance Anticipated: If high resistance is anticipated, managers should lean towards strategies that minimize resistance by involving others more and planning less clearly at the beginning. For instance, involving employees in decision-making can reduce pushback against a new software system.

- Change Initiator’s Position of Power: The change initiator’s power relative to the resisters determines the approach. Less power necessitates moving towards strategies that involve others more and plan loosely at the start. Conversely, stronger power allows for faster, more clearly planned strategies with minimal involvement of others. For example, a CEO with strong influence might implement a new policy quickly and decisively.

- Locus of Relevant Data and Needed Energy: When change initiators need significant information and commitment from others, they should adopt strategies that involve others more and start less clearly planned. This approach ensures they gather the necessary data and energy for successful implementation. For instance, gathering input from various departments can help design a more effective organizational restructure.

- Stakes Involved: High immediate stakes, such as a crisis, require fast, clearly planned strategies with minimal involvement of others to quickly overcome resistance. Lower stakes allow for a slower, more inclusive approach that aims to minimize resistance. For example, during a financial crisis, rapid implementation of cost-cutting measures might be necessary.

Steps for Successful Strategy Development & Implementation

To ensure success, Kotter and Schlesinger suggest these steps to increase chances of success:

- Organizational Analysis: Managers should start by identifying the current situation, problems, and potential causes. This includes evaluating the importance and urgency of the problems and the kinds of changes needed to address them.

- Analysis of Change Factors: Next they should a) understand who might resist the change, why, and how much b) identify who has crucial information and whose cooperation is essential and c) assess the initiator’s power and relationships with relevant parties.

- Selecting a Change Strategy: Based on this analysis, managers should then choose a strategy that specifies the speed of change, the amount of preplanning, and the degree of involvement needed. This also includes selecting tactics for individuals and groups.

- Monitoring Implementation: Finally, managers should closely monitor the implementation process to identify and react to unexpected issues as they arise.

In summary, implementing organizational change is challenging, but understanding the reasons behind resistance can make all the difference. Successful change management isn’t just about having a plan—it’s about involving the right people, being flexible, and continuously monitoring progress. By taking the time to understand the current situation and the potential challenges, managers can create a more inclusive and effective change process.